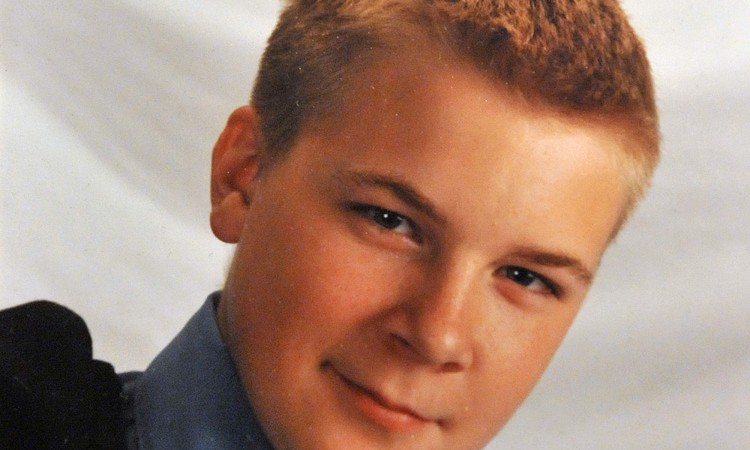

David Koschman

Who killed David Koschman?

Published Feb. 28, 2011

By TIM NOVAK, CHRIS FUSCO AND CAROL MARIN

Staff Reporters

Like a lot of suburban kids, David Koschman wanted to get a taste of Rush Street, Chicago’s fabled adult playground.

So he and four friends — all freshly turned 21 — headed downtown for a Saturday night of bar-hopping. Around 3 in the morning, they decided to call it a night.

As they were leaving Bar Chicago on Division Street that spring night in 2004, they crossed paths with three men, all about 10 years older, and a woman — a group, it turned out, with ties to some of the most powerful people in Chicago. Among the group was then-29-year-old Richard J. “R.J.” Vanecko, a nephew of Mayor Daley.

According to his friends, Koschman bumped one of the men, and the two groups — both later described by a detective as “drunk” and “plastered” — began trading insults and obscenities.

The confrontation ended with a punch. Someone — the police have never said who — hit the slightly built, 5-foot, 5-inch Koschman in the face. Koschman fell backward and hit the back of his head on the street. He died 12 days later from a brain injury.

†††††

Police and prosecutors say that’s because their initial investigation concluded that Koschman was the aggressor and that whoever hit him acted in self-defense.

Still, nearly seven years after the April 25, 2004, confrontation that left Koschman mortally injured, the Chicago Police Department has decided to reinvestigate the case. Investigators began reinterviewing witnesses after a Chicago Sun-Times reporter filed a request Jan. 4 seeking copies of all police reports in the case, under the Illinois Freedom of Information Act.

The police, citing what they described as a now-ongoing criminal investigation, agreed to make public only a heavily redacted crime-scene report. It provides little information other than Koschman’s name and the date and location of the confrontation.

But a Sun-Times investigation has turned up problems with the way the police and prosecutors originally handled their investigation into Koschman’s violent death. Detectives didn’t begin interviewing witnesses until after Koschman died. They didn’t conduct lineups to try to identify who threw the punch until almost a month after it happened. And prosecutors say their files on the case have disappeared.

Now, in what law-enforcement sources say is an unusual move, the police department has assigned the re-investigation of Koschman’s death to a different detective bureau, transferring it from Area 3 to Area 5.

The Cook County state’s attorney’s office says it stands by its initial conclusion that no one should be charged. Though its files are missing, officials say the original prosecutor who recommended no charges be filed still works there. They would not identify him.

“They declined charges, but they can’t find the file?” said Richard Kling, a criminal-defense attorney who is a law professor at IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. “I’ve been doing this for 39 years, literally thousands of cases. I’ve never seen a felony-review file missing. Ever. Never heard of one.

“There’s certainly some red flags,” said Kling. “Like not investigating the case earlier, a missing felony-review file, transferring the case from one area to another and not having lineups until a month later.”

Among the Sun-Times’ findings:

The police reinterviewed Koschman’s four friends on Jan. 17 — one day before the department said in a letter to the Sun-Times that it could not release any information on “crime-scene details, witness and suspect names and statements” because of “the department’s ongoing criminal investigation.’’

Vanecko and one of his three companions ran off after Koschman was hit, according to witnesses and the police. It’s unclear where or when the police found them.

Vanecko declined to talk with the police, though his friends did.

Nearly a month after Koschman was punched, Vanecko appeared in a police lineup at which Koschman’s four friends and another witness could not identify him as one of those involved in the confrontation. One of Koschman’s friends says a detective recently told him that Vanecko had changed his appearance in that time, shaving his head. Also, the friend says the man who struck Koschman wore a hat, though no one wore a hat in the lineup. Koschman’s friends did identify Vanecko’s two male companions as having been present that night but said those men didn’t punch Koschman.

The police department says detectives concluded that Koschman was the aggressor because witnesses told them he charged at Vanecko’s group — a contention that Koschman’s friends dispute, maintaining that Koschman was the victim of a “sucker punch.”

The Cook County state’s attorney’s office, which was headed at the time of the investigation by Richard Devine, a longtime political ally of the Daley family, determined there was no evidence to charge anyone with Koschman’s death, so his staff closed the investigation.

Given how the case has been handled in the past, Koschman’s mother, Nanci, says she has a hard time believing the police actually are re-examining her son’s death. She said detectives haven’t spoken to her since May 2004.

“I’m angry at the people who took his life,” Nanci Koschman said in an interview. “I want someone to say, ‘I’m sorry.’ I’m realistic I’m never going to get that.”

‘A rite of passage’

Nanci and Robert Koschman were married for several years when she learned she was pregnant with identical twin boys. On Feb. 12, 1983, she gave birth to David and a stillborn son. Her doctors told her she wouldn’t be able to have any more children.

The Koschmans raised their only child in a small, ranch home in Mount Prospect. He played baseball, loved the Cubs and stock-car racing and made friends early in life who he remained close with until his death.

On Sept. 24, 1995, Koschman’s father died suddenly as the result of a heart problem. The boy was 12 years old.

Koschman was “very friendly, nice, like a jokester,’’ recalled Lela Bork, who was a classmate at Prospect High School. “I didn’t know anybody who didn’t like him. He was really, really close to his mom. There were nights when we would go out, and he would go to a movie with his mom.”

Koschman had no criminal record.

He was “never any trouble . . . a very spirited young boy, a lot of personality,’’ said Pat Tedaldi-Monti, the high school’s dean. “Absolutely not an aggressive boy at all when I knew him in high school.’’

Koschman graduated from Prospect High in 2001, along with the four friends he would go drinking with on Rush Street three years later.

Two of those friends — Scott Allen and James Copeland — worked with him at an insurance company in Arlington Heights. Koschman was also taking classes at Harper College, and he planned to transfer to Roosevelt University.

The weekend of April 24, 2004, one group of his friends had invited him to join them on a trip out-of-state to see a NASCAR race. It was either that or go with other friends to Rush Street and then, the next day, to a Cubs game. He settled on Rush Street.

His mother didn’t have any problem with the five friends going to Rush Street.

“I loved the city,” Nanci Koschman said. “He learned about Rush Street through me and all my friends saying that’s a rite of passage. I wasn’t a mom who says, ‘Don’t go to Rush Street, you’re going to die there.’ ”

Wouldn’t walk away

The police won’t talk about that night. And Vanecko didn’t respond to interview requests, while his three companions all declined to comment.

But Koschman’s friends — including, beside Allen and Copeland, Dave Francis and Shaun Hageline — agreed to talk publicly for the first time about what happened.

That evening, Koschman, Allen, Copeland and Francis drove down from Mount Prospect to pick up Hageline at his apartment near California and Milwaukee, where they planned to spend the night. They headed to Rush Street, hit a few bars and ended up at Bar Chicago, now known as Detention, a second-floor nightclub at 9 W. Division. Around 3 in the morning, they left the bar.

“We were just walking down the street,” Allen said. “Dave brushed shoulders with some guy. They were drunk. We were drunk as well. Words were exchanged: ‘F-you.’ ‘Screw you.’ ”

Koschman and his friends didn’t know the people they bumped into, a group that included:

Vanecko, who’s named after his grandfather, the late Mayor Richard J. Daley and known as “R.J.” Vanecko is the youngest son of Dr. Robert M. Vanecko and his wife Mary Carol Daley, a sister of the current Mayor Daley. In 1992, the mayor’s son — Patrick Daley — and R.J. Vanecko had pleaded guilty to misdemeanor criminal charges stemming from a brawl at the mayor’s Grand Beach, Mich., second home at which a teenager was hit in the head with a baseball bat. Vanecko, then a senior in high school, held a shotgun during the beating, court records show.

His oldest brother, Robert G. Vanecko, has been involved in two City Hall scandals. Robert G. Vanecko and Patrick Daley have been under federal investigation over their 2004 investment in a sewer-inspection company that landed more than $4 million in no-bid contract extensions from City Hall. Robert Vanecko also co-owned a real estate investment company that’s made millions of dollars in fees for managing $68 million from five city pension funds, a deal also under federal investigation.

Craig Denham, also 29 at the time, who was a LaSalle Bank official and is now a financier in New York City. He later married the sister of the mayor’s son-in-law, Sean Conroy.

Kevin D. McCarthy, then 31, and his wife Bridget, then 26. Her father, Jack Higgins, is a friend of the mayor and a developer who built the city’s police headquarters.

Bridget McCarthy was encouraging her group to walk away, according to Koschman’s friends, who said they were trying to get Koschman to do the same.

“They were arguing,’’ Hageline said. “We were trying to break it up, but it kept going. Dave was a smaller guy. He wasn’t really letting it go. He was being kind of mouthy.

“The guy he was arguing with was bigger than him, and bigger than me. At least 6-1, 6-2. He was definitely the biggest guy in the group.’’

At 6-feet, 3-inches, Vanecko was the tallest in the group, according to Illinois driving records.

“The next thing I know — it was pretty much a cheap shot, really — the guy just clocks him,’’ Copeland said. “There was nothing physical of any kind until this guy throws a punch.’’

Francis said he saw Koschman get punched: “I feel like Dave was kind of walking forward, and he got hit. As far as I remember, his fists weren’t raised. The next thing I know, Dave got hit and fell backward.”

Koschman, who appeared to be knocked out, fell backward off the curb and struck his head on the street. The three older men — including the one who hit Koschman — took off, running south on Dearborn, according to a police report that Nanci Koschman was given in 2004.

Allen said he chased down one of three men and tackled him in front of a police officer. That man was McCarthy, who remained on the scene with his wife.

A fire department ambulance took Koschman to the closest hospital, Northwestern Memorial. That’s where he died 12 days later of what the medical examiner’s office determined were “craniocerebral injuries due to blunt trauma. The manner of death is classified as homicide.’’

‘Somebody said something to him’

After Koschman’s death was ruled a homicide, detectives began interviewing people who’d been on Rush Street. Those witnesses included Phillip Kohler, who had first talked to police the night Koschman was hit.

“I saw a group of guys kind of arguing,” Kohler told the Sun-Times. “There was a kid on the outside. He got really aggravated. I think somebody said something to him. He started jumping up and down. He fell backward and hit his head on the curb. I didn’t see the punch. It seemed like a punch.”

Kohler told the police he didn’t recognize anyone involved in the argument, which he said he and a friend happened upon after leaving a Rush Street bar. Police had him view a lineup on May 20, 2004, but he said he couldn’t identify the man who threw the punch.

A couple of days later, news reports disclosed Vanecko’s involvement.

Hearing Vanecko’s name, Kohler said he then remembered that they had gone to the same high school, Loyola Academy in Wilmette, and had “a couple classes” together.

“I’m surprised the police never figured that out,” Kohler told a reporter. “How did you figure out that we went to Loyola together?”

Another of Vanecko’s group, McCarthy, had graduated from Loyola in 1991, a year before Vanecko and Kohler did.

Koschman’s friends also viewed lineups on May 20, 2004, and picked out McCarthy and Denham but said neither man had punched Koschman. None identified Vanecko.

One of Koschman’s friends, Hageline, told the Sun-Times that his friend was hit by a guy wearing a hat but that no one wore a hat in the lineup. Also, Hageline said a detective recently told him that Vanecko had shaved his head between the night Koschman was struck and the time the lineup was held.

“I didn’t even understand why there was a lineup,’’ Hageline said. “They knew he [Vanecko] was on the scene. They caught his friend [McCarthy] on the scene.’’

‘Not how it happened’

Ron Yawger, the detective who investigated Koschman’s death in 2004, said no criminal charges were filed because no one could identify who punched Koschman.

“I was shocked nobody picked him out of a lineup,” said Yawger, who retired from the police department in 2007 and now works for Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan. “There was nobody who could say he was doing the striking. What you feel in your heart and what you can prove are two different things.

“Everybody was drunk,” Yawger added. “Everybody involved was plastered.”

Phil Cline, who was then Chicago’s police superintendent, said last week that no charges were filed because Koschman was the aggressor.

“At the best, it was mutual combatants,” Cline said. “If the other person is the aggressor, then Vanecko has the right to defend himself.”

Prosecutors agreed, according to a written statement last week from the office of Cook County State’s Attorney Anita Alvarez, who was a top prosecutor under Devine, in response to questions: “All witnesses who were questioned indicated that Koschman was the aggressor and had initiated the physical confrontation by charging at members of the other group after they were walking away.”

The state’s attorney’s conclusion is “incorrect,” Hageline said. Koschman never charged anyone, he said.

“The way they’re describing it is not how it happened,” Hageline said. “Neither of them walked away. There were people who walked away but not the main guys. It was a verbal confrontation. There were cops everywhere. These people really felt threatened? If they really felt that threatened, they could have walked away and found a police officer.”

Koschman’s friends said they can’t understand how the police and prosecutors could think that Koschman physically threatened anyone that night, saying he never threw a punch.

“Self-defense? How could that be?” Copeland said. “My friend would have to have initiated some kind of physical threat — and that never happened. Someone was killed that night, and there was no punishment at all for it. If that punch wasn’t thrown, we wouldn’t be talking about this right now.”

Whoever threw the punch could still be charged with first-degree murder, said Kling, the law professor.

“If I were a prosecutor, one punch is enough for a murder charge,” Kling said. “He probably didn’t intend to kill, which brings it down to involuntary manslaughter. My argument would be that a 6-foot, 3-inch guy knows that a punch to the head can cause great bodily harm.”