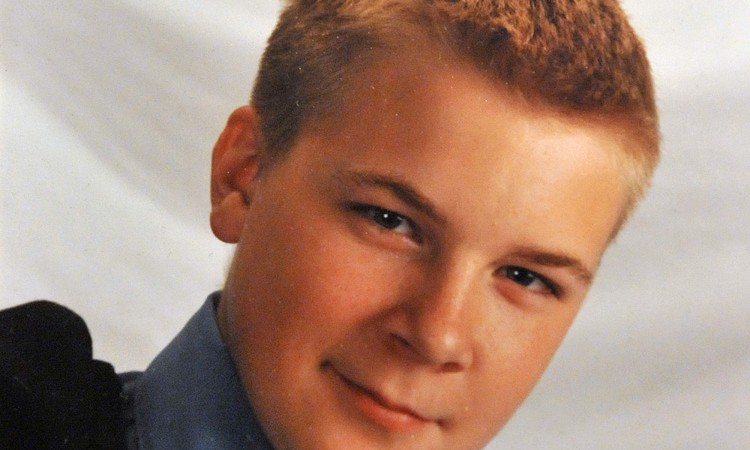

David Koschman

‘CCX’ spells no charges in 204 cases

Published Nov. 11, 2013

By TIM NOVAK and CHRIS FUSCO

Staff Reporters

Five years ago, Dean Goldufsky died inside the home of his boss.

Joseph Cunningham, who helped run his family’s moving company on the Northwest Side, told the police Goldufsky fell down a flight of stairs and died.

But the Chicago Police Department says it was a homicide. Cunningham strangled Goldufsky during an evening of drinking, detectives say.

Twice, they arrested Cunningham, now 33, for first-degree murder. Twice, the Cook County state’s attorney’s office declined to prosecute.

Finally, two years after Goldufsky’s death, the police closed the case, declaring it “CCX” — short for “cleared, closed exceptionally.”

It’s the same way the police closed the case of David Koschman on March 1, 2011. Detectives concluded that Richard J. “R.J.” Vanecko, a nephew of former Mayor Richard M. Daley, delivered a fatal blow to the Mount Prospect man on April 25, 2004, but shouldn’t be charged because he acted in self-defense. It took the appointment of a special prosecutor for Vanecko to be charged last December with involuntary manslaughter.

The Koschman and Goldufsky homicides are among more than 189,000 crimes the police “CCXed” between January 2008 and March 2013, closing the cases without anyone being charged even though the police said they knew who committed the crimes, records obtained by the Sun-Times show.

In some cases, the person who committed the crime had died. In others, such as Goldufsky’s, the police identified a suspect but prosecutors wouldn’t file charges.

More than 47,000 of those cases, or one of every four, involved domestic battery — the largest category of CCX cases. The police also closed thousands of batteries, assaults, shopliftings and burglaries as CCX.

A fraction of the CCX cases in that period were homicides: 179 first-degree murders, 18 second-degree murders and seven involuntary manslaughters.

The police say they follow criteria set out by the FBI for closing a case exceptionally: They have a suspect and sufficient evidence, but “there is a reason beyond our control that precludes us from arresting, charging and prosecuting the offender.”

With murder cases, police spokesman Adam Collins says, “The recommendation is made by a detective and then reviewed up the chain from sergeant to lieutenant to area detective commander to the deputy chief of detectives. The deputy chief makes the final decision to clear a case exceptionally or to decline it, based on the facts, and continue an investigation. For all other cases, the final review is a detective sergeant.”

The Sun-Times sought to review records of all the homicides. The police department said no but agreed to provide records for 15 cases the newspaper randomly selected, including Goldufsky’s.

“That case was closed five years ago,” says Chicago Fire Department Lt. William Cunningham, who owns the moving company where his brother and Goldufsky worked. “I’m not going to be talking. Nor will my brother.”

Goldufsky’s family filed a wrongful-death lawsuit against Cunningham, who settled, paying Goldufsky’s estate $150,000.

Goldufsky’s children and their mother believe Cunningham should still be charged.

“I think it should be reopened,” says Lori Rudick, the mother of Goldufsky’s children. “It just kind of got swept away.”

Joseph Cunningham lived in the upstairs of a single-family home he owned at 6511 N. Natoma. His family also owned the apartment where Goldufsky, 44, lived just around the corner.

Paramedics and police found Goldufsky at the bottom of the stairs inside Cunningham’s home around 9:30 p.m. on Feb. 26, 2008. He was pronounced dead at Resurrection Hospital.

Cunningham had “numerous fresh scratches” on his nose, cheek and neck, according to the police, though Cunningham denied having any scratches, telling police any blood on his face came from Goldufsky vomiting on him as he performed CPR to try to save him.

Cunningham, who was on court supervision for DUI, and Goldufsky, who had served time for burglary and theft, had been eating and drinking for about three hours, according to police reports. Cunningham’s roommate, Katherine Dillon, came home around 8:15, and Goldufsky left about an hour later, Cunningham told the police.

He and Dillon told the police they heard a noise from the stairwell and found Goldufsky. He wasn’t breathing and had no pulse, so Cunningham began CPR, they said.

Dillon told the police she scratched Cunningham’s face while trying to get him to stop doing CPR when paramedics arrived.

Detectives interviewed a downstairs neighbor, who said she heard “loud banging and things dropping” in Cunningham’s apartment around 6 p.m. and that her ceiling fan had been shaking. Around 9:15, she heard a loud noise in the stairwell and recognized Cunningham’s voice.

“Don’t do this to me, wake up, wake up?” the neighbor recalled Cunningham saying, then a woman asking, “Should we call the police?”

Dr. J. Lawrence Cogan of the Cook County medical examiner’s office found Goldufsky had injuries to his larynx and a fractured bone in his throat, as well as injuries to his head, chest and extremities and a separated cervical disc. “The cause of death is strangulation,” he wrote in ruling the death a homicide.

A week later, on March 6, 2008, Cunningham’s lawyer had another pathologist, Dr. Shaku Teas, do a second autopsy on Goldufsky. Teas concluded Goldufsky “died as a result of spinal cord injuries sustained as a result of a fall down the stairs.”

Four days after that autopsy, Joseph Cunningham transferred ownership of the house where Goldufsky lived to his brother William Cunningham.

On July 16, 2008, crime lab results found that Goldufsky’s fingernail clippings contained DNA that most likely came from Cunningham, according to the police.

Cunningham was arrested on July 24, 2008, but released when Assistant Cook County State’s Attorney Robert Heilingoetter wouldn’t approve charges before Cunningham’s pathologist finished her report. Detectives got it on Dec. 19, 2008, and rearrested Cunningham on Dec. 29, 2008. He was released the next day when Heilingoetter wouldn’t approve charges, putting off a final decision.

Five months later, on May 7, 2009, Heilingoetter told detectives he wouldn’t charge Cunningham because he couldn’t determine Goldufsky’s cause of death and because Cunningham never confessed.

The state’s attorney’s office wouldn’t commen.

On Jan. 11, 2010, the police CCXed the case, concluding Cunningham killed Goldufsky based on the scratches on Cunningham’s face, the DNA and the neighbor’s statement about the commotion. The detectives’ report says they “found the statements given by Cunningham and Dillon to be untruthful” about Goldufsky falling down the stairs.

“It makes me so angry,” says Goldufsky’s mother, Sharon Kvistad. “My son wasn’t the most perfect human being, but he didn’t deserve what was done to him — and he didn’t deserve to have it covered up this way.”

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

RELATED CONTENT

Get the ebook “The Killing of David Koschman: A Watchdogs Investigation.” Download now

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________In