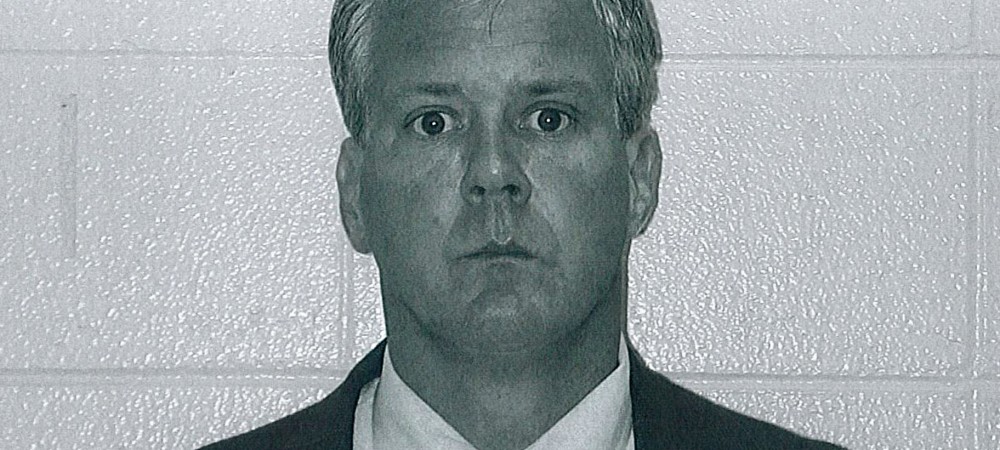

Lt. Denis P. Walsh

‘Missing’ file ended up at cop’s house

Published Feb. 18, 2014

By TIM NOVAK AND CHRIS FUSCO

Staff Reporters

With the heat on in the high-profile David Koschman homicide case, the original Chicago Police Department case file — a file that had been presumed lost, then suddenly surfaced — ended up in a brick bungalow on the Northwest Side.

It was taken there by the owner of the home, Lt. Denis P. Walsh, a well-connected cop with a troubled past. Walsh has now been tied to four instances of missing records in the case, for which former Mayor Richard M. Daley’s nephew Richard J. “R.J.” Vanecko began serving a 60-day jail sentence Friday after pleading guilty to involuntary manslaughter.

The file had been missing for months — possibly years — when it mysteriously turned up one summer’s night three years ago on a shelf in the police station at Belmont and Western.

The officer who reported finding it? Walsh.

He told investigators for the special prosecutor in the Koschman case, Dan K. Webb, that he alerted his commander and the department’s chief of detectives.

And then, Walsh said, he held onto the file for about three weeks, at some point taking it home.

All of this was going on as city of Chicago Inspector Joseph Ferguson was reviewing whether the police mishandled the original investigation of the Koschman case in 2004 and also their 2011 re-investigation. The 2011 police probe ended as the first one had, without any charges filed — and the police falsely concluding that Vanecko acted in self-defense when he punched Koschman during a drunken confrontation on April 25, 2004.

Why Walsh was involved at all in the 2011 police re-investigation isn’t clear. The case had been taken away from his detective division and assigned to another group of detectives, according to Webb’s recently released report detailing how police and prosecutors mishandled the case.

After first refusing to talk with Webb’s investigators last year, Walsh ended up speaking to them under a proffer — a form of immunity that protected him against being charged with a crime for anything he told them.

All of this, laid out in bits and pieces in Webb’s report on the case, is now being sifted through by Ferguson.

Mayor Rahm Emanuel — who was in office when Walsh says he took the files home in 2011 — has said he is awaiting Ferguson’s recommendations before deciding whether to discipline Walsh and five others in the police department. Webb said he decided not to file criminal charges against them over their handling of the Koschman re-investigation because he couldn’t prove guilt “beyond a reasonable doubt.”

“Without any actual testimonial or documentary evidence demonstrating that Walsh played some nefarious role in arranging his discovery of the original Koschman homicide file (or perhaps that he earlier prevented its discovery, or perhaps altered the file in some fashion after its discovery), there is nothing close to proof beyond a reasonable doubt that would support charges against Walsh,” Webb wrote.

In all, Webb found four instances in which the police files on the case are believed to have been missing — with Walsh involved each time.

Here’s a rundown on the missing files:

Jan. 4, 2011 — Ronald E. Yawger, the retired detective who handled the Koschman investigation in 2004, calls someone at Area 3 headquarters. It’s the same day the Chicago Sun-Times files a request to see the police reports on Koschman’s death. Yawger’s original files should have been at Area 3.

Jan. 4-12, 2011 — Area 3 Cmdr. Gary Yamashiroya asks Walsh to find the files. Walsh says he can’t find them. Yamashiroya later finds a manila folder containing Koschman case reports in his credenza — but “not the original Koschman homicide file.” Also, it’s missing documents including interviews detectives did with some witnesses hours after Koschman was hit. Yamashiroya later says Walsh was present when he found the file; Walsh says he can’t remember.

Jan. 13, 2011 — The missing file prompts Constantine “Dean” Andrews, the police department’s deputy chief of detectives, to assign another detective division to re-investigate the Koschman case. Even though Walsh’s detectives are no longer handling the case, Walsh is told to contact Yawger about the 2004 investigation.

Jan. 18, 2011 — Walsh calls Yawger twice.

Jan. 26, 2011 — Walsh sends Yawger a text message.

Feb. 9, 2011 — Though the case was taken away from Walsh’s team of detectives, Walsh gets an email “update on the Vanecko case” from Area 5 Det. James Gilger, who’s heading the re-investigation.

Feb. 28, 2011 — The Sun-Times publishes its first of dozens of stories on the Koschman case. Gilger submits his report, concluding thta Vanecko punched Koschman in self-defense and shouldn’t be charged.

March 1, 2011 — Andrews closes the case.

March 4, 2011 — The city releases some Koschman police reports to the newspaper, though documents are missing — which the department doesn’t disclose.

March 10, 2011 — Walsh tells Andrews in a memo he supports closing the case without charges: “The analysis of the investigation supports the findings. The offender has been identified, and it has been determined that the offender was taking actions to defend himself.” Again, it’s not clear why Walsh is involved, since the case has been closed and Walsh’s detectives didn’t handle the re-investigation.

April 15, 2011 — Ferguson demands the police give him “all original detective interview notes [GPRs] from the David Koschman investigation.”

April 20, 2011 — Walsh calls Yawger.

June 28, 2011 — Yawger has “a more than four-minute telephone conversation with Area 3 (and possibly Walsh himself).” Yawger later tells grand jurors he had “no idea who I spoke to” that day, and Walsh didn’t recall contacting Yawger after January 2011.

June 29, 2011, 9:39 p.m. — Walsh “reportedly” finds “the original Koschman homicide file . . . on a wooden shelf in [Area 3’s] Violent Crimes sergeants office. The blue binder was reportedly sitting (conspicuously displayed) on a shelf (that had been searched previously) near other Area 3 homicide files which were all housed in white, as opposed to blue, three-ring binders.” Walsh later tells investigators “the blue three-ring binder was ‘clearly’ ‘put there’ by someone to be easily discovered.”

According to Webb, “The documents in the Koschman blue binder homicide file are not in the same order as its table of contents, which indicates that the file may have been rearranged at some point.”

Some documents are missing from the file, though it does contain a report in which Yawger identified Vanecko as “V Dailey Sister Son.” Walsh calls Yamashiroya, who alerts Chief of Detectives Thomas Byrne. No one tells Ferguson or Gilger, who closed the case without having seen the original file.

Yawger later tells grand jurors “when he last saw the original homicide file for the Koschman case, it was not in a blue binder.”

June 30, 2011 — Yawger visits Area 3. While waiting to see Walsh, he “reportedly” finds his Koschman “working file” in the detective locker room “in a box labeled with (Yawger’s) name on it.” Walsh notifies Byrne.

According to Webb, “It remains unclear why Yawger’s ‘working file’ was not discovered in CPD’s initial searches in 2011 of Area 3, especially because, according to Yamashiroya, the locker room area had previously been searched. During his interview with [Webb’s investigators], Yamashiroya stated that it was both ‘embarrassing’ and ‘shocking’ that missing files (both the discovery of the ‘original’ Koschman homicide file as well as Yawger’s ‘working file’) were turning up with little explanation for their sudden appearance. During his interview, Walsh told [investigators] that he was ‘surprised’ that Yawger gave him a second set of Koschman files only one day after the Koschman blue three-ring binder had been discovered.”

July 1, 2011 — Yawger meets with Ferguson’s staff.

July 20, 2011 — Walsh notifies the police Internal Affairs Division of the “original” missing file he says he found on June 29. According to Webb, “Walsh reported the original Koschman homicide file, ‘believed to have been lost, was obviously not lost’ and instead had been ‘removed and returned in violation of department rules and regulations’ by an ‘Unknown Chicago Police Officer.’ Despite what Walsh wrote, during his interview . . . he stated he did not necessarily agree with his superior’s order for him to file an IAD complaint, noting that, ‘on its face, is there a real rule violation?’ ”

Gilger and his partner Nick Spanos review the file that evening, deciding it doesn’t change their conclusion that Vanecko hit Koschman in self-defense.

July 25, 2011 — The Sun-Times reports detectives closed the Koschman case without reviewing the original file.

Aug. 24, 2011 — IAD Sgt. Richard Downs interviews Walsh about the missing file. Downs closes the IAD case the next day without any disciplinary charges.

Dec. 14, 2011 — Nanci Koschman asks a judge to appoint a special prosecutor to investigate her son’s death.

April 23, 2012 — Webb is appointed.

Dec. 3, 2012 — A grand jury indicts Vanecko. Webb continues to investigate whether police and prosecutors mishandled the case.

April 24, 2013 — Webb learns of a fourth “missing” file when Det. Robert Clemens, who worked the case in 2004, says that, “between late February 2011 and late July 2011, he found a Koschman homicide file on a table near the photocopier in the detective area at Area 3. . . . When shown a color photo of the ‘original’ Koschman homicide file Walsh reportedly found in 2011 (the blue three-ring binder), Clemens testified that the photo depicted something different than the file he found at Area 3 in 2011.

“Clemens testified that when he gave Walsh the homicide file, he told Walsh, ‘You don’t want this out on the floor,’ to which Walsh responded, ‘This thing’s got legs.’ ”

Walsh later tells investigators “he had no memory of any of Clemens’ assertions.”

This file has never been found.

Aug. 13, 2013 — Walsh surprises Webb’s staff, telling them someone else was in the room with him when he found the original file — and that he eventually took it home. He says his former partner, Sgt. Thomas Flaherty, was there when he found the blue binder — and says he had told this to Yamashiroya and “probably” also Byrne and Andrews.

Yamashiroya later says he doesn’t remember Walsh telling him that anyone was with him when he found the file. Walsh says he never told Internal Affairs because: “You don’t volunteer things” to IAD.

According to Webb, Walsh says “he asked Byrne to take and maintain the file, but Byrne refused and ordered Walsh to keep it.” Walsh “then locked the file in a cabinet in his Area 3 office and later took the file home and placed it in his personal safe for some period of time, until William Bazarek (first assistant general counsel to CPD) told him that keeping an original homicide file at his home was not a good decision.”

Aug. 21, 2013 — Flaherty says “he observed Walsh walk in to the room [on June 29, 2011] and watched him pull a blue binder from the bookshelf. Flaherty recalled Walsh exclaiming profanities indicating Walsh’s surprise that he had just discovered the missing Koschman homicide file.”

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

KOSCHMAN COPS’ RUN-INS WITH LAW

LT. DENIS P. WALSH

Ten years ago, police Lt. Denis P. Walsh was charged with felony criminal sexual assault, accused of groping and bruising a gas station clerk near Kalamazoo, Mich.

The victim disappeared, and prosecutors let Walsh plead guilty instead to two misdemeanors, assault and battery, and pay a $600 fine.

Walsh was suspended for 30 days by Supt. Phil Cline. He later was promoted to a job supervising detectives on the North Side.

Walsh comes from a family of Chicago cops. His dad was a deputy police chief. His brother is a lieutenant. His father-in-law is a retired cop. His sister-in-law was a member of Mayor Richard M. Daley’s security detail.

Walsh, 50, is paid $115,644 a year. He got another $32,248 in overtime last year.

RETIRED DET. RONALD E. YAWGER

Ronald E. Yawger was an undercover Chicago detective when he was arrested by the FBI nearly 30 years ago, accused of providing security for a cocaine dealer. Yawger was acquitted after testifying he didn’t know his informant was carrying about a half pound of cocaine when he drove him in an undercover police car to meet an undercover federal agent.

The city never disciplined Yawger, who retired from the police department in 2007 with a pension that now tops $70,000 a year.

A month after his retirement, Yawger, now 62, started work as an investigator for Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan. He makes $76,548 a year. His wife works for the Illinois Workers’ Compensation Commission. Their son was an unpaid intern last year for Gov. Pat Quinn.

The lead detective in the 2004 David Koschman case, Yawger testified under immunity before a grand jury that indicted Richard J. “R.J.” Vanecko.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________