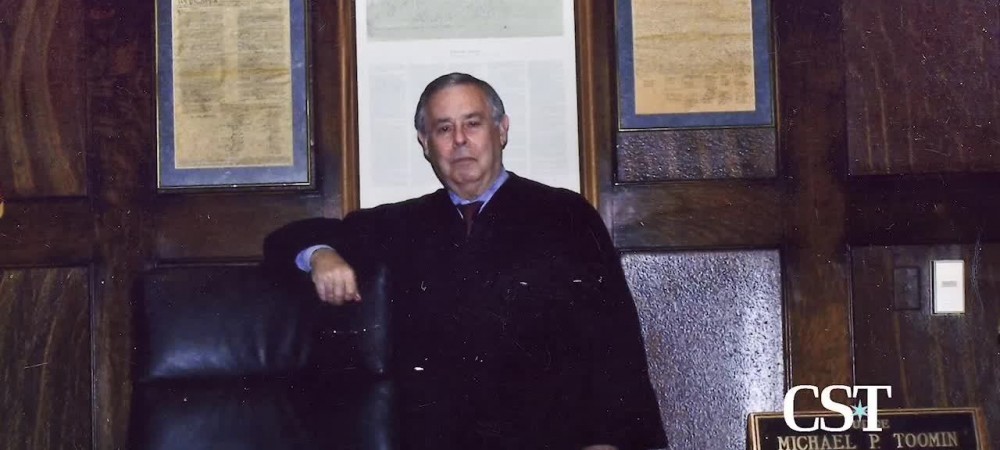

Judge Michael P. Toomin

Editorial: Release the report

Published Friday, Oct. 11, 2013

Richard J. Vanecko, charged with involuntary manslaughter in the death of David Koschman, will get a fair trial. Of this we have no doubt.

Whether the rights and interests of the public will be respected as fully is entirely another matter.

On Thursday, the Chicago Sun-Times and WMAQ-Ch. 5 asked a Cook County judge to unseal a special prosecutor’s report on his investigation into Koschman’s death in 2004. Vanecko, accused of throwing the punch that led to Koschman’s demise, is a nephew of former Mayor Richard M. Daley.

As a matter of law and the public’s right, we believe Judge Michael P. Toomin has no choice but to unseal the report. Its focus is solely the questionable conduct of police and county prosecutors nine years ago, matters entirely irrelevant to Vanecko’s trial.

Given all the troubling questions surrounding the Koschman case, Cook County’s entire criminal justice system operates under a cloud of suspicion. The public has every reason to believe that those with clout get favored treatment. That cloud will not dissipate until the special prosecutor’s report is unsealed, all the facts are revealed, and efforts at reforming the system can begin.

As attorneys for the Sun-Times and WMAQ-Ch. 5 state in court documents filed Thursday, “The public’s understanding is a crucial safeguard against official misconduct.” To delay the release of the special prosecutor’s report until after Vanecko’s trial, set to begin in February, is to keep the public in the dark.

Only in the most exceptional circumstances should public records be kept from the public, and the Koschman case doesn’t come close to meeting that standard. Even the sealing of the Pentagon Papers during the Vietnam War era was deemed unjustifiable by the courts, though the Nixon Administration warned that their release would endanger national security.

Moreover, the Sun-Times and WMAQ-Ch. 5 lawyers make a convincing argument that Judge Toomin violated court procedures when he failed to give advance notice and hold a hearing before sealing the report.

Toomin placed the report under seal at the request of its primary author, special prosecutor Dan Webb, who said he feared its findings would stir up so much pretrial publicity that Vanecko couldn’t get a fair trial. Any jury pool, he argued, might be tainted, though he provided no studies or facts — as required by law — to back that up.

As a seasoned prosecutor, Webb must know better. He surely knows that potential jurors in high-profile criminal cases almost always bring with them pre-conceived notions. That does not irreparably prejudice potential jurors, nor is the remedy to try to squelch big headlines by sitting on public documents.

As stated in the documents filed Thursday, it is “unthinkable” in modern society that “any qualified juror” would be “oblivious” to big events in the news. One might as easily find 12 unicorns to sit as jurors. What matters, as the lawyers say, is that jurors “lay aside impressions or opinions and render a verdict based upon the evidence presented in court.”

Jurors do that every day.

Good lawyers — and Vanecko’s lawyers and Webb are very good — manage to select impartial jurors through careful vetting and questioning. They may even request a change of venue. And they understand that the menace of pretrial news reporting to a fair trial is routinely overstated.

As the media lawyers argue, it is hard to imagine that the findings of the Webb report, made public, would be “any more prejudicial at a trial” than the last several years of news coverage of Koschman’s death. On the contrary, the Webb report deals exclusively with the conduct of the Chicago Police and Cook County state’s attorney’s office in investigating the death — not on particulars of the homicide itself. The report’s findings likely have no bearing on Vanecko’s guilt or innocence.

But what if they do? What if there is something in the report that really should be kept secret in fairness to Vanecko?

Then — and only then — would it be appropriate for Judge Toomin, after giving proper notice and holding a hearing, to make the tightest of redactions, cutting not a word more than necessary.

And then he should release the report.

The Chicago Sun-Times’ investigation into the curious story of David Koschman’s death has been a 2?-year exercise in unearthing secrets.

Let there be no more.